Lakewood Church, USAs største. Kilde: wiki commons

Christian Lycke, førsteårsstudent ved landskapsarkitektur på NMBU, medlem i nettredaksjonen

I USA på 50-tallet vokste det frem en ny bevegelse innen kirkedesign: megakirken. Senere begynte man å bygge det som kalles campus churches, som har mye til felles med megakirker (og på et vis kan en campus church være en megakirke), men har flere fasiliteter, som gymsaler, forskningslab, skolerom, bowlingbaner, kino, svømmehall og helvetes mye annet som ikke pleier å være forbundet med kirker. Megakirkene kan spore sin begynnelse hos mange protomenigheter, men Metropolitan Tabernacle i London, som ikke hadde tilhørighet til The Church of England og telte mange tusen medlemmer i siste halvdel av 1800-tallet, virker som en klar foregangsfigur for disse menighetene. Kriteriene for å regnes som megakirke er å ha minst 2000 besøkende ukentlig, være protestantisk - gjerne evangelisk, og har som regel flere bygninger med diverse funksjoner spredt utover. Det vil si at de fleste megakirker med, for eksempel 30 000 medlemmer, ikke pakker alle inn i ett bygg på søndag, men har flere messer i løpet av uka på forskjellige plasser. Det er menigheten som gjør kirken mega, ikke byggene, selv om de ofte vitner om størrelsen.

Metropolitan Tabernacle i London, ca. 1858.

De største megakirkene finnes nå i Sør-Korea, der Yoido Full Gospel Church er størst med 253 000 medlemmer. Den største i USA er Lakewood Church i Houston, og er langt nede på lista over de største i verden, med fattigslige 45 000 medlemmer.

Det som skiller megakirkene fra svære postmodernistiske kirkebygg rundt omkring er hvor utilitære de er. Det er som regel menigheten som finansierer dem, og dermed stramme budsjetter. De ligner på kjøpesentere og community colleges, ligger i utkanten av byer og reflekterer den amerikanske kjørekulturen, med digre parkeringsplasser og mange tilbud samlet på ett sted.

Solid Rock megachurch, Cincinnati. Credit: Joe Shlabotnik

Kote tok en prat med arkitekt og planlegger Barry A. Parks, som fra 80-tallet og frem til 2011 jobbet med en rekke megakirker, blant annet Second Baptist Church Houston, som er blant de fem største megakirkene i USA. I dag er han husarkitekt ved en college i Texas, eventuelt Senior Project Director at Lone Star College – University Park Campus, hvis man skal være presis. Barry er en fet dude som maler og reiser på fritida og vedlikeholder en hjemmeside som er verdt å sjekke ut: http://www.barryaparks.com/

(All tekst som følger er på engelsk)

Hey Barry! Thanks for taking the time to chat with us.

We’re having a look at religious architecture in a series of articles, and it struck us that we don’t have a lot of insight into the relatively new movement of megachurches and campus churches - which is viewed as a North American phenomenon, but has spread and become especially popular in South-Korea, the Philippines and several Latin American countries.

K: How did you get into designing and planning church buildings?

B: I was convinced from a very early age that I wanted to be an architect. I had native skills as an artist, strengths in math, and very good spatial visualization abilities. I grew up in a small town in the mostly rural state of Arkansas and my exposure to architecture (under even the most liberal use of that term) was very limited -- almost exclusively homes, schools, and churches. Thus I imagined that I would grow up and all my energies would be spent working on those building types.

Upon graduation from high school I left my boyhood home and moved to Houston, Texas to attend architecture school at the University of Houston College of Architecture. A few months after graduation with a Bachelor of Architecture degree I was able to land a job with a firm called Calhoun, Tungate, Jackson & Dill (later C.T.J.& D. Architects) and it seems like that is where much of my education really began. This firm was, I believe, the oldest in the city at that time and had a tremendous background in a number of categories: churches, education (mostly colleges and universities), and various governmental/military facilities (including multiple phases of master planning the NASA campus south of Houston). It was work on two projects in particular that I credit for launching my career as a church architect.

Those projects, both based in Houston, were for Second Baptist Church and First United Methodist Church, and were quite different in many ways but highly visible and large in scale.

The Second Baptist Church Houston, rendering by E. Reichert and C.T.J.& D. Architects

Ultimately, the Second Baptist project would yield the largest church facility in the country -- a record that held for a number of years. Harold Calhoun, founder of the CTJ+D firm, was a member of this congregation and had been involved in the earlier projects on this 40-acre site in a very affluent area of Houston. The expansion project that we took on culminated in the addition of a new 6,400-seat sanctuary, classrooms shared between the church's private high school during the week and Sunday School groups who meet before or after services on Sunday, expansive health-club and sports facilities, administrative offices, music rehearsal spaces, a small TV production studio, expanded parking, new playing fields for sports, as well as re-modeling within a number of pre-existing spaces. The total cost in the mid-1980s was $34 million. I was originally brought into the firm as a draftsman for a university classroom and lab building, but the lead designer in the department quickly took me under his wing to assist him in the master-planning process for Second Baptist Church in Houston.

Interrupting this project, an explosion and fire did heavy damage within the sanctuary and adjacent spaces at downtown Houston's First United Methodist Church. At that time, this was believed to be the Methodist church with the largest membership in the world. The circa 1910 building lost a wall of Tiffany-style stained glass, organ pipes melted, a section of balcony and much of the plaster ceiling collapsed, and heat and smoke damage permeated the building. CTJ+D's Ed Reichert was both a member of this church and had designed numerous improvements to the facility over the previous years, so it was no surprise that the request was made for him to lead the effort for restoration. He again brought me in for support and appointed me the role of incorporating improvements into the space as he focused on the restoration of the balance. In particular, I was charged with some more pedestrian goals such as increasing the lighting necessitated by video transmission of services, adding mechanical cooling to offset the heating from the lights, updating the sound system within the space, and designing a stage lift which would allow the pipe organ console to be lowered into the basement below. This last goal was part of a bigger architectural reworking of the entire chancel to increase the space for the choir from about 30 people to 100 and to configure the chancel platform for greater flexibility of use including installation of an overlay stage surface for orchestra, drama, or dance. The design I produced under Reichert's watchful eye created a new focus for the space.

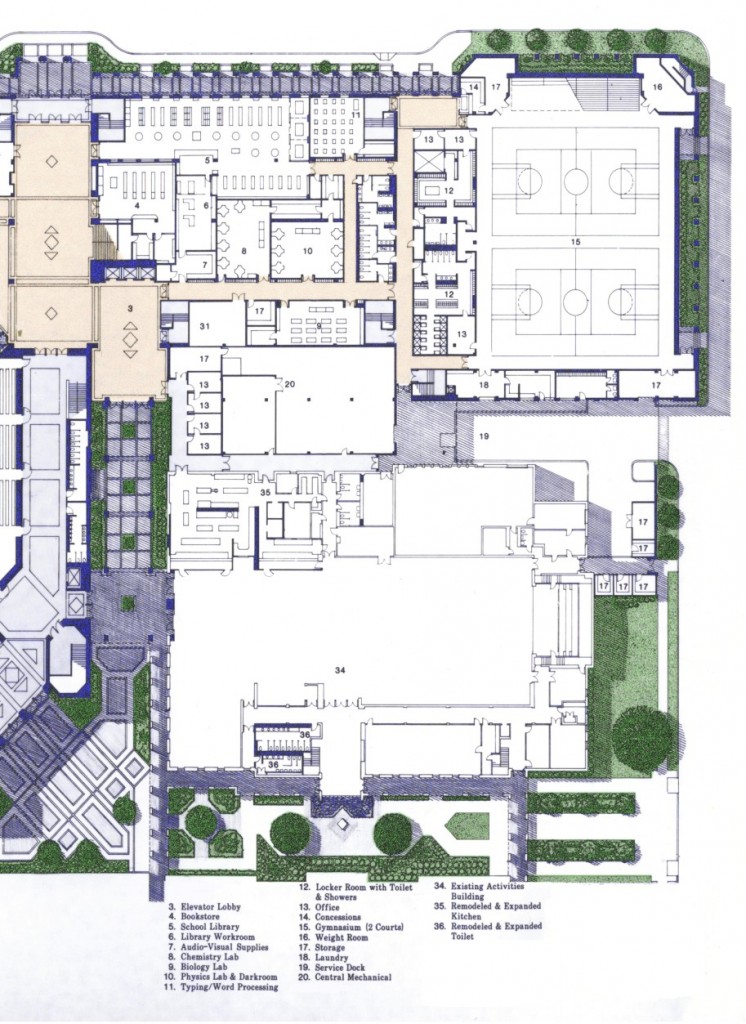

As we wrapped up that design work and began the daily oversight of the contractor charged with reconstruction, others in the firm continued the work to document the Phase 1 portion of the Second Baptist project. I shifted between trips to the construction site in downtown and laying out the (Phase 2) balance of the Second Baptist plans to define the school classrooms, school library, a church bookstore, and the family life center (which included a simple theater, rooms for aerobics, exercise equipment, crafts, ping pong and billiards, locker rooms with spas and saunas, four handball courts, an 8-lane bowling alley, two running tracks, a double basketball court gym, and the control desk to manage the area).

Ultimately both projects were well-served with both talented architects and very good contractors, and by the time each was successfully completed, I felt that I was rather well-educated in what it meant to be a church architect.

K: What are the some of the trickier aspects of planning and completing campus churches/megachurches?

B: As far as I was concerned the biggest challenge of any church project -- no matter the scale -- was trying to make sure that the design response was specifically matched to the congregation that I was serving. Did the response work within and build on architectural cues from existing structures on site (if such existed)? Could church members see specific aspects of the design that grew out of conversations and observations that we had in the early stages of design? Did the facility allow the congregation to better do the things that they were already doing and saw as fundamental to what set them apart from other churches?

As churches grow in scale, of course, the challenges grow in both obvious and non-obvious ways. Often these may include political difficulties with zoning or planning restrictions as these facilities are often considered unwelcome neighbors introducing noise, light, and traffic to surrounding residences. This requires upfront work with a multitude of authorities having jurisdictional controls as well as grassroot efforts to build or improve relationships with non-members in the area near the site. Usually codes will dictate parking requirements for the large assembly occupancies and traffic impacts will need to be considered and often measured for governmental review. Most large developments will need to develop approved means for retention of stormwater as large amounts of the site are rendered impervious. As parking increases, one needs to study the means for safely separating vehicular and pedestrian movement.

Some of Barry's work on Lake Forest Church - Huntersville. From barryaparks.com.

Within the building, one should use available tools to help congregants (and visitors who have never been in the building before) confidently find their way to and between their venues (worship center, classroom, childcare center, fellowship hall, family life center, etc.). At larger scale, buildings are often segmented, with each area having one or more stand-alone entries. This, in turn, raises concerns about security control.

For the designer, the matrix of connections with consultants grows exponentially and will include many rather technical advisors: acousticians, theatrical and lighting professionals, stage designers, broadcast technicians, perhaps commercial kitchen designers, the aforementioned security consultant, etc. as well as structural engineers with sufficient experience to confidently design long spans -- and often -- complex frames, and the usual stable of civil, mechanical, electrical, plumbing, and life safety system engineers, landscape architects, and interior designers. If the architect is seen as the conductor of an orchestra, he suddenly realizes just how many parts must be directed.

Rotating one's view in the opposite direction, the architect for this kind of work has an enormous client base. While his or her point of connection with the congregation is usually limited to a small building committee, the number of people who recognize "their church architect" can be very large, underscoring the sense of responsibility and -- particularly on local project -- the inability to escape scrutiny even during planned "off-the-clock time." From the perspective of the client, churches blessed with quick growth look at that rate of growth and realize that they must expand the facilities to stay viable. The growth trend typically suggests volumes of spaces that the church simply cannot yet afford.

Put another way, the money available does not match the perceived need. Very often, these projects need to commence as master planning exercises based on the assumption of multiple phases of development. Also, while amenities need to be scaled up, it is important to search out any economies available in building systems. Wherever possible, one should lean toward straightforward structural framing systems. To the extent that weather allows, one should consider the use of exterior spaces for circulation and, perhaps, public gathering areas. Invariably, the least expensive building is one that is not built. One should work with the church to consider how modifications to program schedules might best utilize what space is built -- even if this incurs up-front expenses for making the constructed spaces more functionally flexible.

K: How do consider your own work in relation to the long history of church building?

B: I recognize that for the most part I've been working along the edge of a very large movement. While my formative experience working on Second Baptist is noteworthy for a number of reasons including its continuing position as the largest Baptist church, Houston is currently home, according to the Hartford Institute of Religious Research, to 37 megachurches including the largest congregation in the US at Lakewood Church. The number of campus-formatted churches is larger still. Had I remained in Houston after Second Baptist was finished rather than moving and practicing from more than 25 years in the less populated state of North Carolina, perhaps I would have had an opportunity to take a part in more megachurches through my career. As it was, I instead filled my portfolio with a wide scale projects, each with rather distinct personalities. I believe that the congregations I served feel like I supported their cause and developed facilities that surpassed their goals. New buildings, of course, always impact the way the occupants relate to each other and act out their ministry. The best of my work not only helped the church to do what they imagined that they wanted to do better, but also offered options for doing things that they had not previously imagined.

K: Modern American churches (and a lot of European ones, too) differ greatly from classical church building styles. From your writings you seem to have an extensive knowledge of historical church architecture. When planning halls of worship, what (classical) elements would you consider?

B: One must remember that American was strongly influenced by the early arrivals of post-Reformation pilgrims and other dissenters. Their rejection of the Catholic church, Church of England, and other State Churches also included a rejection of the ornament connected with those entities.

An under-appreciated exception to the rejection of historic church ornamentation does exist. The first Baptist Church in the United States (at Providence, Rhode Island) was clearly modeled on the almost-contemporary Saint Martin in the Fields Church by James Gibbs in London, England. Gibbs had given the front a classical temple porch and shifted the tower and spire from the crossing of the transept forward to rest on the structure immediately behind the porch. The design appeared in a style book that was not only the source for the Providence church, but which, over time has served as the un-credited model (column-supported porch supporting a gable, with a steeple centered behind) for perhaps 90% of American Baptist churches, no matter how humble the scale or construction materials. Notably, other denominations also picked up the same design shorthand in significant numbers.

Saint Martin in the Fields Church. Credit: David Castor

As all of my work has been with non-Catholic churches, I have found that I have spent time on the front end of our conversations suggesting that Gibb's work is not the "ultimate expression" of what it might mean to "look like a church." While I rarely found a rejection of ornamentation on theological grounds in the congregations I served, there tended to be concern about cost, misunderstandings about the scale that is needed in a large space, and a general sense of distrust of anything "too different."

Even so, certain design prejudices I carry have often found their way into my work. Like Abbot Suger, I strongly prefer natural light to punch into the worship space. I want art (mural, stained glass, even window frame patterns) to help reinforce the sense of place and the underlying message. I also try to shape the experience with my choice of words: "nave" instead of "auditorium" or "worship center;" "chancel" instead of "stage;" "narthex" instead of "lobby" or "foyer." The use of these terms allows me the opportunity to talk about what those words mean, where they came from, and how others in the past viewed the act of worship. I found the extent the congregation is interested in having those conversations serves as a litmus test for what comfort there might be for exploring architectural options that might be referential to earlier churches.

The emphasized function of the new spaces differ dramatically from the earlier models. Expectations of clear sight lines, distortion-free sound, and comfort overshadow desires to insert the mystical. Ultimately, my experience has been limited mainly to making respectful nods toward the preceding models.

K: ... and do you try to infuse a spirit of holiness, of the sacred - or are you more pragmatic?

B: For many ministers and congregations, the revelation of the holy comes through scripture, inspired preaching, music, and the acts of worship such as communion and baptism. For these, architecture is background and, often, neutral. Of the 60 or so church projects where I played a lead role, there were surprisingly few where I was given the opportunity to begin to layer the space with architectural elements meant to reinforce the church's message. In one case, Lake Forest Church in Huntersville, NC, the pastor and his building team wanted a building that was a reflection of their understanding of man's relation to God. The church's mission statement is that they want to be church "for people who have given up on church, but have not on God." I was charged to design a building which draws parallels between an incomplete and unpolished congregation coming together to God in acts of worship. Thus building materials and forms are rough, raw, and incomplete. Floors are stained concrete. Railings are sealed rusted pipe. Ceiling tiles were randomly left out of ceiling grids. At the same time, the space was designed to be welcoming. At the entry to the worship space a lodge-like lobby with fireplace reinforced this idea.

In a more traditional setting, my work at Ardmore Baptist Church in Winston-Salem, North Carolina was predicated on a directive from the pastor to design a sanctuary which supported worship through use of traditional and new symbols. This challenge allowed me to set the sanctuary behind a transitional parvis or paradise, to create a narthex that was distinctive from an adjacent lobby, to shape the room in a cruciform plan and to reference the early church connection with ships (the architectural term "nave" shares the same root as the word "naval") in the treatment of a reversed keel-like roof framing system. Placement of components typically aligned in one orientation in Baptist churches (communion table, pulpit, and baptismal pool) were re-organized across the front of the chancel to emphasize a connection between those three elements and the Trinity.

K: Did you tend to work with a standard/favoured set of materials, or do they differ from project to project?

B: For the limited budgetary reasons noted above, material selections were rather pedestrian and selected on the basis of value. Under those limitations, I usually tried to add visual interest with pops of detail. This might be with, for example, over-scaled lighting fixtures, design of a railing system, or even signage.

K: As an example, what kind of building materials did you use or plan to use on the Second Baptist Church?

B: The Second Baptist project in the early 1980s, like many churches that I've worked on since, was made up of a steel frame faced with brick on metal stud backup. Most interior walls were painted gypsum drywall on metal studs. Most flooring was carpet. Ceilings were mostly drywall or acoustic panels in grid.

The project was of a scale, however, that allowed some exceptional choices. The flooring in the narthex was composed of a pattern of two types of granite tiles -- something that is much more widely sourced now than it was at that time. Much of the detail within the space (columns and capitals, ceiling treatment, etc.) was custom-formed gypsum-reinforced fiberglass. Within the interior of the narthex and sanctuary, over 10,000 square feet of faceted glass designs filled two walls and much of the ceiling. On the exterior, details were added to the fields of brick with cement-reinforced fiberglass. To cap the building, a copper dome was topped by a steel pipe finial shaped into a cross piercing a globe which was gold-leafed.

The classrooms. A small portion of the project. Visit Barry's site for the rest. Credit: C.T.J.& D. Architects

K: As employers, what is it usually like to work with churches? Are you answering to a whole congregation, or a few select people?

B: As a church determines the need for a building program, they typically appoint a building team or committee to lead the process of planning for the facility. It seems that larger projects often have smaller committees -- perhaps three-to-five members -- while smaller projects seem to be under the purview of groups of perhaps two dozen members. They get the assignment based on background in the construction industry, because they are viewed as influential decision makers for the church, or perhaps because they are expected to be major contributors when it comes time to make payments.

I found that the job of helping the committee understand the process and their role in it was mostly an enjoyable one. They approach the task with gravity and some trepidation, but invariably are looking for good results and want to feel that they have contributed to that end. These people can provide enormous amounts of important background information about the church's past. This is where I can quickly find out about any preconceived solutions that might need to be addressed. They serve as a sounding board for testing new ideas. Once a direction is set, they become important cheerleaders to the rest of the congregation. To summarize, I find that developing a trusting relationship with this laity is vital for a successful result.

K: Campus churches often seem to have more in common with schools, malls, music venues and theatre stages than your typical Western protestant or catholic church. Do you think that these facilities change the church-going experience? If so, how?

B: The problems to be addressed in a large-scale church are very much like those addressed in other public buildings like malls and schools. I am very comfortable with adopting the best lessons learned from those venues like schools, malls, coffee shops, and amusement parks. It seems almost impossible to not draw strong comparisons between a church and a theater. However, theologically I think that congregations need to be led to understand that the two differ in a very fundamental way: theaters wrap a stage so that the audience can observe actors in their roles, while churches fill the seats in their sanctuaries with congregations called to be more that observers -- they are called to be the actors in the act of worship (led by ministers and others on the chancel) before a God who is present to receive the worship. Churches that don't work to make that distinction clear miss, I believe, the opportunity to communicate something vital about our call to worship.

K: Finally, I see that you enjoy travelling. Which architectural destination is on the top of your list of places to visit?

B: To date, my European travels have been limited to multiple trips to France and England with a singular trek into Scotland. My favorite building is Paris' Sainte-Chapelle, both for the impact it has on me and for the joy of watching the expressions of those who come into the upper chapel for the first time. I find that I'm drawn especially to the gothic churches throughout France - their daring, the long-term commitment, their diverse personalities, the overlay of history, and the ingrained symbol languages on display.

After 35 years of talking about it, my wife and I are flying to Venice in a few weeks. We will spend three weeks working our way through museums, churches, and probably a few "ristoranti" in Venice, Florence, Siena, Orvieto, and Rome. The trip will culminate with an exploration of The Vatican. Now that is a megachurch!

Credit: Gnosne